Effective training stimulus requires working near physiological muscle exhaustion.

For most training adaptations, effective training stimulus pushes you in the direction of temporary muscular failure. Regardless of rep volume, consistently working near muscular failure will reliably yield productive results.

So, in that sense, rep range doesn’t really matter as much, right? Well, no – there’s a catch:

This only way this works is if we “fail perfectly.”

Physiological muscle exhaustion is a result of “ideal failure.”

No effort is entirely useless. A hard set doesn’t simply become ineffective because of a technical compromise – for better or worse, there’s always some benefit to be gleaned.

That said, training operates in the currency of stimulus: time and work capacity constraints place urgency on getting the most benefit out of every set. Consequently, how we fail has a heavy impact on net training progress.

${component=BasicCard}Ideal Failure

Fatigue accumulates rep over rep until the speed of contraction slows to a snail’s pace.

Hitting ideal failure usually means that a muscle has done all it can against the provided resistance, and is approaching true physiological failure.

${component=BasicCard}Unideal Failure

Rep failure is caused by:

- Breakdown in technique

- Exhaustion of stabilizing muscles

- Inability to initiate the next repetition

- Stalling at a harsh sticking point

Hitting unideal failure means that a muscle still has output capacity against the provided resistance, but is gatekept by one of the above factors. As a result, the muscle is not approaching true physiological failure.

Making “ideal failure” easier to reach: The Length-Tension Relationship.

The Length-Tension Relationship dictates the relative strength of muscles at corresponding muscle lengths. In practical terms, this means:

- A shortened or lengthened muscle is typically weaker, and thus can move less load.

- A muscle in the middle of its range is stronger, and thus can move more load.

To demonstrate the real sets-and-reps impact, let’s compare 2 different rep schemes for low cable face-away curls. This exercise biases the lengthened range of the bicep.

A max effort set of 4-6 reps will likely fail at the very beginning of the final rep. The weakest position of this exercise covers this exact range. Consequently, the failure was caused by an inability to overcome the weakest position of the exercise, likely leaving the muscle with untapped output capacity: the load effectively undercut stimulation via the sticking point.

A set of 12-15 reps is more likely to fail at any other point. The dominating effect of the exercise’s weakest position is significantly dampened, enabling greater expression of training output. Under this scheme, failure more likely results from exhausting the muscle’s output capacity, reaping the maximal stimulus on offer.

Using the Length-Tension Relationship to reach true failure more often.

Successfully leveraging this concept means that you’ll need the correct pairing of variables – sets, repetitions, load, and exercise selection. Let’s take a look at how to structure these variables on a practical level.

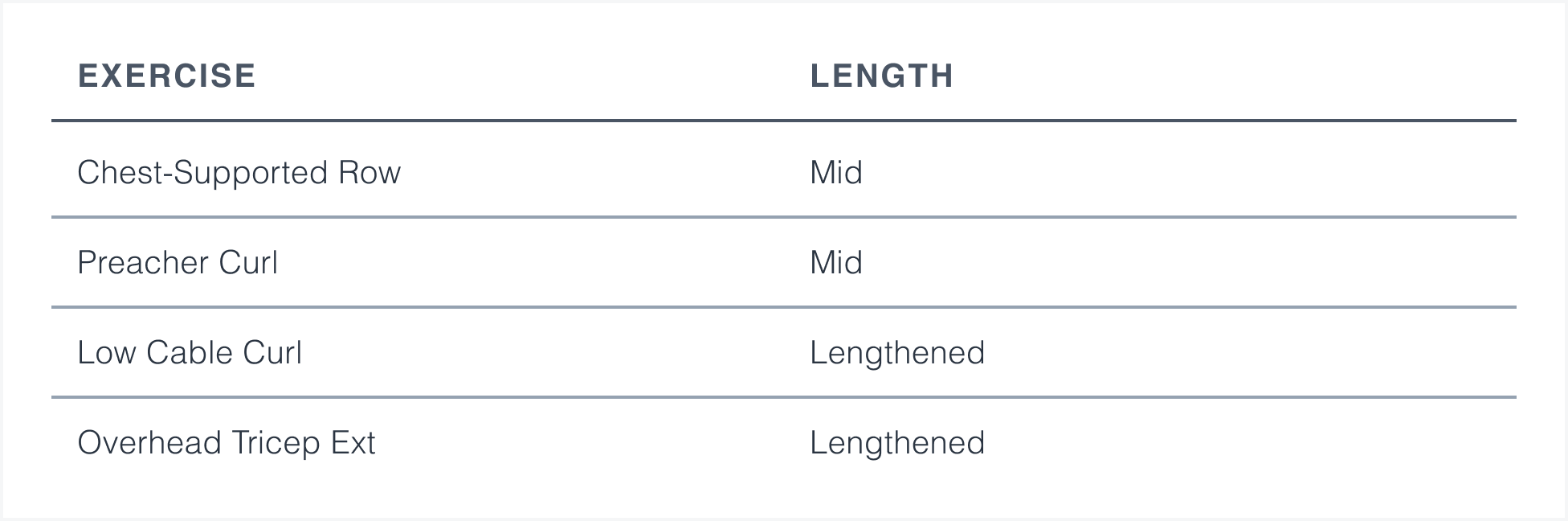

${component=Step,id=1}Classify your programming by muscle length.

Examine each exercise in your program, and classify its position on the length-tension relationship according to the operating length of the target musculature: shortened, mid-range, or lengthened.

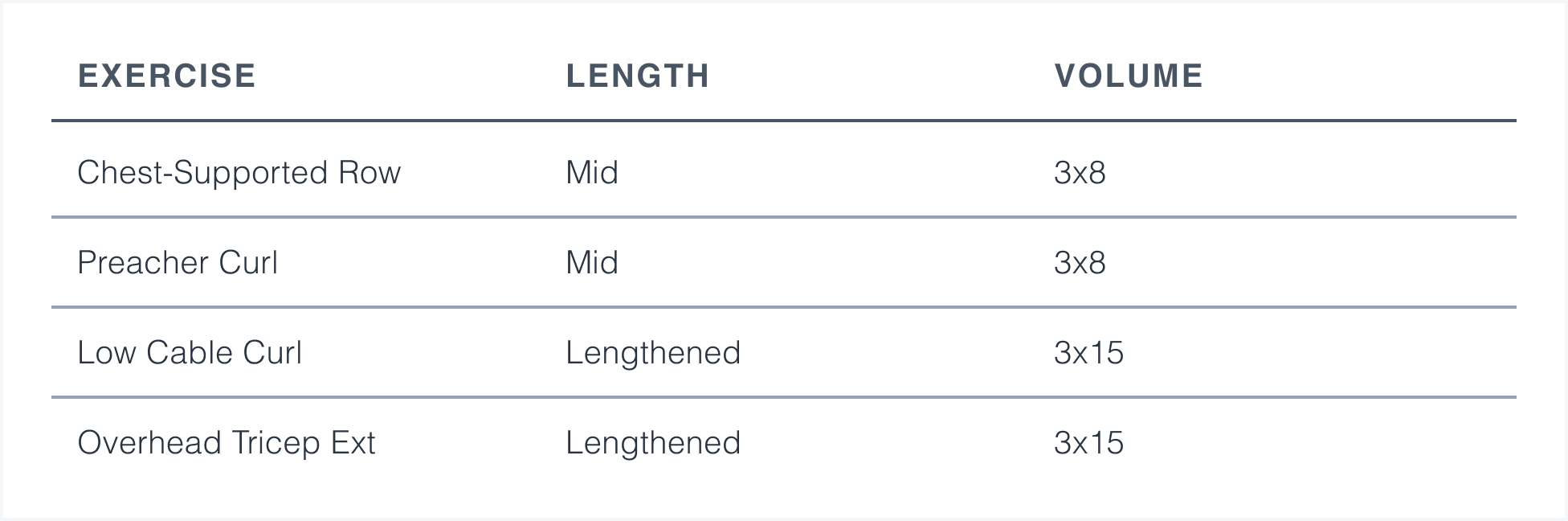

${component=Step,id=2}Set volume & load according to length bias.

End range exercises typically benefit most from 10-15 rep sets with lighter loads.

Mid-range gets the most benefits from 6-10 rep sets with heavier loads.

A lighter load doesn’t mean less effort. Doing more reps accounts for the target musculature’s length-tension relationship and the exercise’s strength curve.

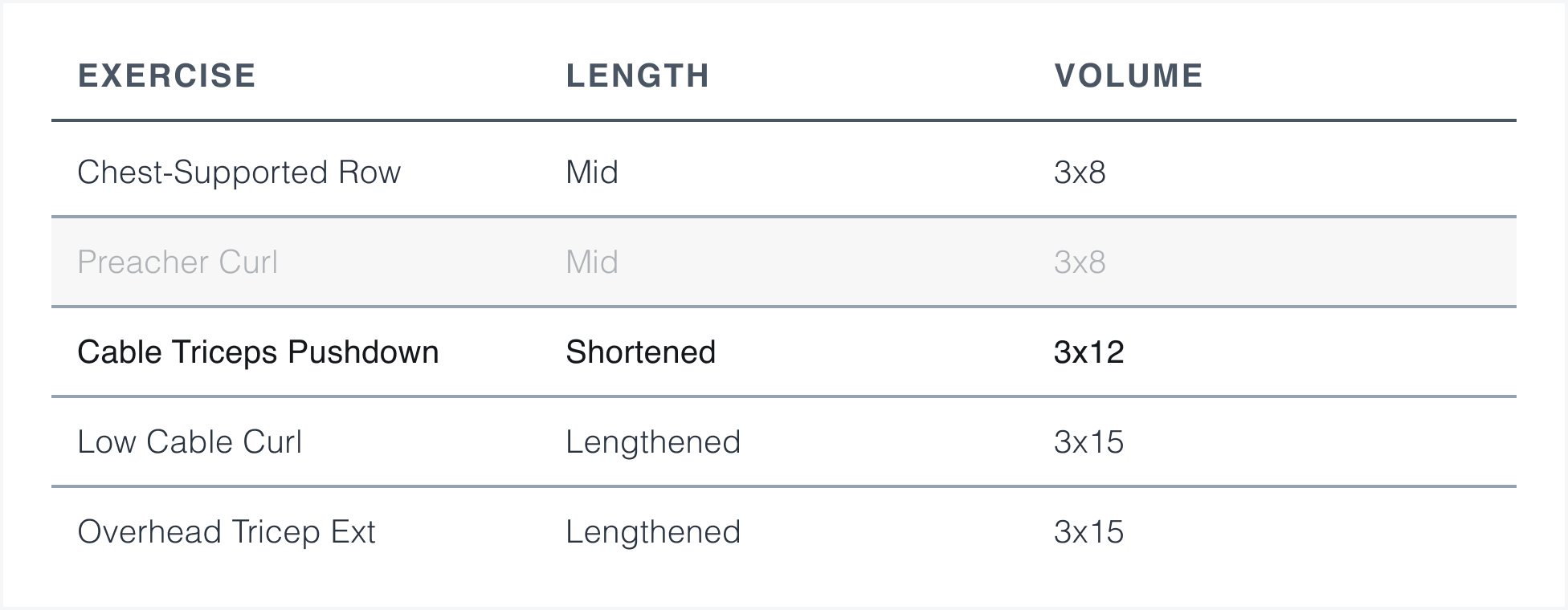

${component=Step,id=3}Replace redundant exercises, double down on training productivity.

You don’t need an exercise for each range of every muscle group – eliminate overlap and redundancy where possible, thereby opening training bandwidth.

Double down on training productivity— Take advantage of the freed bandwidth to add exercises targeting other muscles.

${component=Step}Send it.

Nailing the ideal form of failure makes an enormous difference in gains, and this can’t possibly be overstated. Getting this right is where the Length-Tension Relationship shines.

Harmonizing all programming variables and execution factors unlocks the virtuous cycle of gains, which snowballs into higher rates of overall progress.

${component=BasicCard,ordinal=}The virtuous cycle of gains.

- More bouts of reaching perfect failure

- More net muscle stimulation per workout

- More gains triggered by greater adaptation